Līdaku iela, 23. Talsi, LV-3201

Latvija

Sacrifices have been common religious practices all around the world since prehistoric times. Nevertheless, there was an extensive and sometimes heated debate over whether medieval reports on sacrifices in the Viking Age, especially human sacrifices, refer to actual events or were fabricated reports to denigrate the pagan faiths.

Academic criticism applies to medieval chroniclers such as Rimbert, Thietmar von Merseburg, Adam Bremensis and Saxo Grammaticus, who reported human sacrifices and war sacrifices in the Viking Age. All of them were Christians, writing at the end of the Viking Age or during the Medieval ages. None of them has witnessed the supposed rites, but all of them were always very clear on their religious convictions and negative appreciation of pagan faiths. Besides, their reports are not independent.1

Heimskringla‘s and Jómsvíkinga saga‘s credibility on the matter has also been challenged for different reasons.2

Meanwhile, films like “The 13th Warrior” and series like “Vikings” and “Vikings – Valhalla” romanticize human sacrifices in the Viking Age, often showing victims willing – and even happy – to participate in the sacrifice.

These blockbusters seek to adapt ancient accounts to current sensibilities, conveniently omitting some significant details. In Ibn Fadlan’s popular account (to which we will return shortly), the girl being sacrificed and drugged is, to use a consciously anachronistic term, gang-rapped.

Gro Steinsland recognizes human sacrifices as reality during the Viking Ages and interprets them not as an everyday public religious practice but as resources used during war and crisis.

War sacrifices would not necessarily be an explicit sacrifice performed before the battle – a commander would, for instance, dedicate and consecrate the enemy warriors to Óðinn with his spear before the combat. Thus, those slain by his army became the sacrificial offering.3

This last symbolic and mythical association has been recognized among sacrifices, war, and the god Óðinn, mostly due to the works of Snorri Sturlusson.

In the Ynglingasaga, Snorri affirms that Óðinn instituted sacrifices shortly after arriving in the northern lands, along with other religious practices, including cremations and the erection of monuments:

| One sacrifice was to be held towards winter for a good season, one in the middle of winter for the crops, and a third in summer; that was the sacrifice for victory. | Þá skyldi blóta i móti vetri til árs, en at miðjum vetri blóta til gróðrar, it þriðja at sumri, þat var sigrblót. |

Snorri also affirms that Óðinn marked himself with the point of a spear before dying, and those who did so would join Óðinn in the afterlife.4

In the Poetic Edda, stanza 138 of Hávamál tells about the self-sacrifice of Óðinn, when he hanged for nine nights in Yggdrasil, the world tree, wounded with a spear.

Snorri’s Ynglinga Saga, in chapter 25, tells the story of King Aun, who sacrificed nine sons to Óðinn in exchange for longer life – for each son sacrificed, Óðinn granted him additional ten years of life.5 In this case, there is no direct connection with war, but the human sacrifice remains in connection to Óðinn.

This Odinic symbolism of the sacrifice is shared in other sources than Snorri’s works. For instance, the Gautreks saga, a later legendary saga, contains the popular and dramatic story of Starkaðr, the old, when he sacrificed his friend and benefactor Vikar. Trying to cheat his destiny and Óðinn, Starkaðr stages a mock sacrifice of Vikar, with calf intestines as substitutes for a rope and a fragile reed replacing a spear. During the staging, however, Óðinn transforms the elements into the real ones, and Vikar dies.

While performing the act, Starkaðr says: “Now, I give you to Óðinn”.6

When it comes to the actual ritual, independent sources such as Snorri and Adam Bremensis agree on some fundamental points, notwithstanding the criticism regarding the complete veracity of the ancient religious practices described in them. However, war sacrifices to Óðinn before the battle are far less commonly mentioned in other sources than would be expected. In contrast, some reference mentions sacrifices to Óðinn unrelated to war.

Most sources mention the number nine in connection to the sacrifices. The religious symbolism of the number is widespread in the Northern traditions and can also be found in neighbour cultures, from the Balts to the Anglo-Saxons. 7

Both Snorri and Adam depict the expectation that the king should take part in the rites of sacrifices, including ceremonial meals and drinking taken inside cultic buildings.

Thus, it has been argued that the kings’ presence would have been considered fundamental to a sacrifice, as they may have been mediators between the human and divine spheres.8

Rulers refusing to sacrifice would create considerable tension among their subjects, as in the case of the Hákonar saga góða, when the Christian King Hákon, the good, tries to avoid participating in the sacrificial feasts in Hlaðir.9

In extreme cases, kings were sacrificed as the last resource after prolonged times of drought or famine.

Snorri’s Ynglinga Saga, for instance, describes two instances of sacrifices of kings:

In chapter 15, King Dómaldi was sacrificed after three years of famine. In the first year, they sacrificed oxen; in the second, human sacrifices without results.10

Later, in chapter 43, King Óláfr was also sacrificed by his own subjects:

| King Óláfr was not in the habit of sacrificing. The Svíar were dissatisfied with that and thought it was the cause of the famine. Then the Svíar mustered an army, made an expedition against King Óláfr, seized his house and burned him in it, dedicating him to Óðinn and sacrificing him for a good season. | Óláfr konungr var lítill blótmaðr. Þat líkaði Svíum illa ok þótti þaðan mundu standa hallærit. Drógu Svíar þá her saman, gerðu fǫr at Óláfi konungi ok tóku hús á honum ok brendu hann inni, ok gáfu hann Óðni ok blétu honum til árs sér” |

These two references are peculiar compared to other Snorri’s writings, as they explain the sacrifice as a reaction to famine but affirm the rite was dedicated to Óðinn. Otherwise, they agree with the general corpus describing sacrifices as a recurrent practice during proving times and regarding the king’s role in the ceremony.

Thietmar von Merseburg, writing before 932, claimed that the Danes had their main cult centre in Zealand, in Lejre, where every nine years, humans and animals were sacrificed:

| Every nine years, in the month of January, after the day on which we celebrate the appearance of the Lord [6 January], they all convene here… and offer their gods a burnt offering of ninety-nine human beings and as many horses, along with dogs and cocks – the latter being used in place of hawks. | …ubi post VIIII annos mense Ianuario, post hoc tempus, quo nos theophaniam Domini celebramus, omnes convenerunt, et ibi diis suimet LXXXX et VIIII homines et totidem equos, cum canibus et gallis pro accipitribus oblatis, immolant… |

Adam, writing ca. 1070 concerning the Temple at Uppsala, reports that the sacrifices were carried out every nine years, lasting nine days. The religious agrees in some detail with the previous authors and adds other information on his own. His description includes a didactic division of sacrifices and offerings according to their function and the deity to which they were dedicated:

| For all their gods there are appointed priests to offer sacrifices for the people. If plague and famine threaten, a libation is poured to the idol Thor; if war, to Wotan; if marriages are to be celebrated, to Frikko. It is customary also to solemnize in Uppsala, at nine-year intervals, a general feast of all the provinces of Sweden… The sacrifice is of this nature: of every living thing that is male, they offer nine heads … The bodies they hang in the sacred grove that adjoins the temple. | Omnibus itaque diis suis attributos habent sacerdotes, qui sacrificia populi offerant. Si pestis et famis imminet, Thorydolo lybatur, si bellum, Wodani, si nuptiae celebrandae sunt, Fricconi. Solet quoque post novem annos communis omnium Sueoniae provintiarum sollempnitas in Ubsola celebrari … Sacrificium itaque tale est. Ex omni animante, quod masculinum est, novem capita offeruntur… Corpora autem suspenduntur in lucum, qui proximus est templo. |

Ibn al Fadlan (c. 879 – c. 960), a Muslim traveller, reported on the customs of the Rus and other people from the Volga route. His description of a Scandinavian sacrifice, completely independent from the Latin authors, became hugely popular as being retold in Michael Chrichton’s book, becoming a film starred by Antonio Banderas.

In the account, Ibn al Fadlan narrates the sacrifice of a slave girl to accompany her dead master, among the Rus Varangians in the Volga, probably of Swedish origin. According to the report, the girl was intoxicated, raped by six men, and then died while stabbed by a seeress, held and strangled by the men.

However, there are dozens of accounts written by Muslim travellers quoting sacrifices in the Viking Age among the Rus.

The Gutasaga, written in the 13th century on the island of Gotland, refers to sacrifices of human beings and animals and differentiates between a great sacrificial act that involved human sacrifices and the whole island and a smaller one carried out by the local assemblies, which involved cattle, food and drink.11

Other Icelandic sources than Snorri’s and the Jómsvíkinga saga show that the theme of human sacrifices was well known to the Icelandic poets and authors. Human sacrifices are mentioned in the Eyrbyggia saga,12 the Landnámabók,13 the Vatnsdæla saga,14 the Kristni Saga, and Ólafs saga Tryggvasonar en mesta.15

Finally, once more, the Landnámabók refers to a certain Þórólfr heljarskinn, a man also mentioned in the Vatnsdæla saga, who sacrificed humans. Curiously, the reference in chapter 17 of the Vatnsdæla saga is similar in voice to the Heimskringla when referring to Jarl Hákon´s sacrifice – the saga affirms there was a “suspicion” that Þórólfr offered human sacrifices.

Human remains have been found in bogs in Northern Germany, Poland, and Denmark since ca. 8,000 a.C., and sacrifices can be attested since the Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

In Denmark alone, ca. 560 bog bodies have been found. About 145 of these bodies can be dated to the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age. Often the bodies display violent deaths such as signs of death by strangling. Some smashed skulls, however, were recently re-interpreted as being smashed post-mortem by the pressure of the surrounding bog. 16

Two female bodies were found in the Oseberg Ship in Norway, but it is unclear what the relationship between the women was and if one was sacrificed to the other.17

Archaeological excavations demonstrate that Lejre was the seat of Danish royal families since the Iron Age, but the religious significance of the place was not confirmed.

At the place, two skeletons were discovered, probably a chieftain with his slave. One skeleton was adorned with armour, jewellery, and weapons, while the other had feet and hands bound and was decapitated.

Probably the slave was unwillingly sacrificed to accompany his dead master.

A similar finding was discovered in Dråby, Denmark, with the exception that the master was a woman accompanied by goods, jewellery, and a decapitated slave.

The region along the nearby lake Tissø, whose etymology is connected to the god Tyr, is more promising as a sacred place. Evidence of sacrificial fests was discovered on the lake’s west bank at the magnate’s residence, including weapons, jewellery, tools sacrificed in wells and streams, and vestiges of cult objects, animals, and humans, in cult places.18

Excavations in Trelleborg pre-dating the construction of a Viking fortress around 980-981 revealed a sacrificial site. A small enclosure was discovered close to three of the sacrificial wells, and it was suggested that the place was used for performing rituals before depositing the victims in the wells.

A possible symbolic connection of sacrifices in wells to Óðinn cannot be discarded, as the god gained wisdom after drinking at Mímir’s well and sacrificing one of his eyes.19

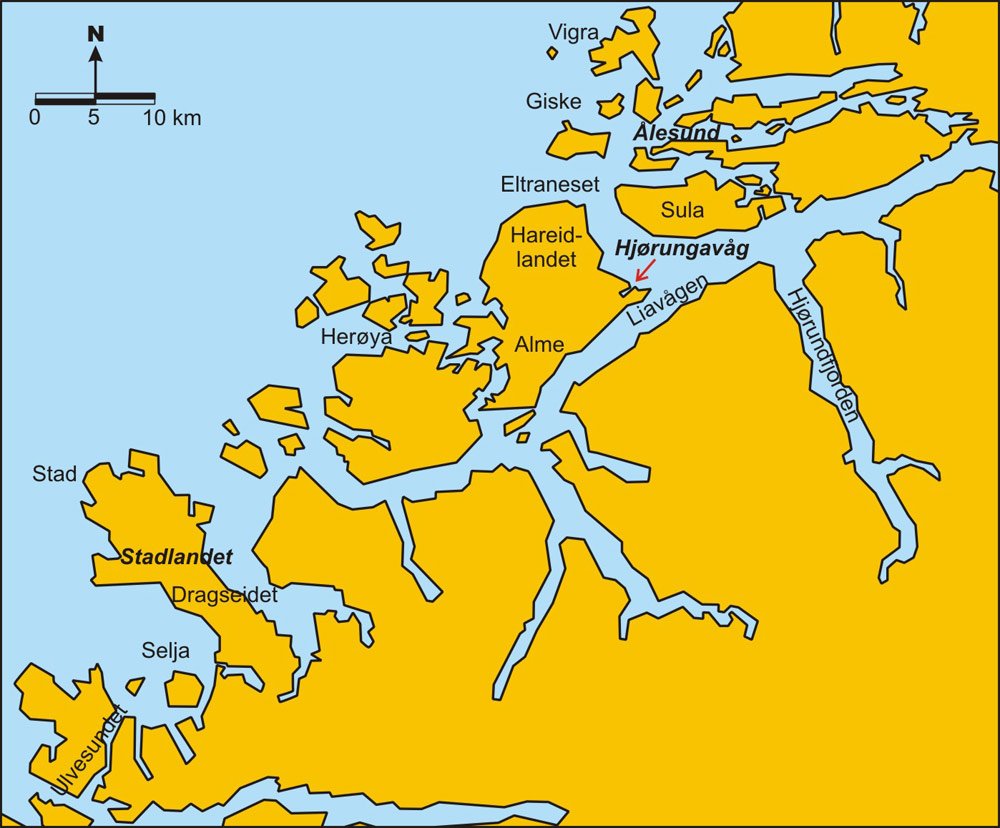

In the year 986 was fought the semi-legendary Battle of Hjǫrungavágr on the coast of Norway. A Danish fleet, sent by Haraldr blátǫnn (“Bluetooth”) Gormsson and led by the Jómsvíkings, was defeated by the Norwegians, led by Jarl Hákon Sigurðarson.

Prior to the battle, Denmark was ruled by Haraldr Gormsson (king from ca. 958 to his death ca. 985/6), who converted to Christianism after the 960s.

Parts of Norway, including the south and Oslo fjord area, were under Haraldr’s control but were ruled de facto by Jarl Hákon Sigurðarson (ca. 937-995), Haraldr’s vassal after the death of Haraldr Gráfeldr in ca. 970.

According to the Gesta Danorum and the Heimskringla, Haraldr Gormsson was defeated by Emperor Otto II ca. 974 and was forced to be baptized. Hákon had supported Haraldr against the Emperor and defended the Dannevirke, but at the time of Haraldr’s defeat, he had already sailed out, intending to return to Norway.

In the aftermath, Haraldr sent word to Hákon – a staunch pagan – to return to Denmark. Haraldr forced him to be baptized and ordered the jarl to convert all of Norway, sending clerics with him on his way back home.

Later in the same year, Hákon returned to Norway and rebelled.

These conversion reports, however, do not reflect what most probably occurred and were influenced by a fabrication of Adam Bremensis, as Haraldr’s conversion must have happened about ten years before.

According to the Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar, in his return to Norway, Hákon abandoned the clerics, raided several regions and carried out a war sacrifice to Óðinn. As Snorri wrote,

| Then the jarl felt sure that Óðinn had accepted the sacrifice and now it would be a propitious time for the jarl to fight. | Þá þykkisk jarl vita, at Óðinn hefir þegit blótit ok þá mun jarl hafa dagráð til at berjask. |

King Haraldr Gormsson died in 985 or 986 during a rebellion carried out in Denmark by his son Sveinn Haraldsson tjúguskegg (“Forkbeard”). In Saxo, Haraldr was still alive during the time of the battle of Hjǫrungavágr, but that information disagrees with other sources.

Many sources dealt with Jarl Hákon’s life, before and after the battle, in more depth and far more accurately than the Gesta Danorum. That includes prose works such as the Heimskringla, the Jómsvíkinga saga, Fagrskinna, and poetry such as the Jómsvíkingadrápa (ca. thirteenth century) and Vellekla. Ágrip offers details on Jarl Hákon’s later life but is silent on the battle.

The Flateyjarbók and Heimskringla provide detailed accounts of the opposition among Olaf Tryggvason and Jarl Hákon in contraposition of Christianity and Paganism, while Saxo emphasizes the events around Haraldr Gormsson and the Conversion of Denmark.

In the battle of Hjǫrungavágr, the Danish invading fleet and the Jómsvíkings were defeated. The victorious Norwegians were led by Jarl Hákon and his sons, Eiríkr and Sveinn.

Besides generalities such as who fought on each side, who were the main characters, who won and who lost, one striking detail is mentioned in every account of the event. Before the battle, Jarl Hákon sacrificed one or two of his sons to achieve victory.

The Jómsvíkinga saga offers one of the most detailed accounts of the event, with some particularities of its own.

The saga, similarly to the Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar, tells that prior to the battle Jarl Hákon not only reverted to paganism after his forceful baptism by the Emperor and led others under his rule to do the same but sacrificed more than before:

| … but some reverted to the paganism and error they had practised before, because of the jarl’s overbearing. But Jarl Hákon cast off faith and baptism and then became the greatest apostate and heathen worshipper, so that he had never performed more sacrifice than he did then. | … en sumir gingu aftur til heiðni og villu þeirrar er þeir höfðu áður, fyrir sakir ofríki jarlsins. En jarlinn Hákon kastar þá trúnni og skírninni og gerðist þá hinn mesti guðníðingur og blótmaður, svo að aldregi hafði hann meir blótað en þá. |

Before the battle against the Jómsvíkings, Hákon asked for help from Þorgerðr Hǫrðatrǫll, a popular yet somehow mysterious character found in several Icelandic texts. Þorgerðr, however, was angry with Hákon and refused to aid him. Hákon gradually increases the value of his offerings until she accepts them:

| But she turns a deaf ear… and he now asks her to accept from him various things by way of sacrifice, and she will not accept them … And it comes about in the end that he offers a human sacrifice, and she is not willing to accept what he offers her as a human sacrifice… Now he begins to increase his offers to her, and it reached the point where he offers her any other man except himself and his sons Eiríkr and Sveinn. But the jarl had a son who was called Erlingr and was seven years old and promised to be a fine man. But it comes about in the end that Þorgerðr accepts his offer and chooses the jarl’s son Erlingr. … and then he has the boy taken and puts him in the hands of his thrall Skofti, and he puts the boy to death in the manner usual for Hákon and as he told him to do. Now … “I know now for sure,” says he, “that we will defeat the Jómsvíkings … for … I have made oaths for victory to both the sisters, Þorgerðr and Irpa … ” | En hún daufheyrðist við bæn jarls … og býður hann henni nú að þiggja af sér ýmsa hluti í blótskap, og vill hún ekki þiggja… Og þar kömur því máli loks að hann býður fram mannblót, en hún vill það ekki þiggja er hann býður henni í mannblótum … Tekur nú og eykur boðið við hana, og þar kömur máli, að hann býður henni alla menn aðra, nema sjálfan sig og sonu sína Eirík og Svein. En jarl átti son þann er Erlingur hét og var sjö vetra gamall og hinn efnilegsti maður. En það verður nú of síðir, að Þorgerður þiggur af honum og kýs nú Erling son jarls … og lætur síðan taka sveininn og fær hann í hendur Skofta kark þræli sínum, og veitir hann sveininum fjörlöst með þeima hætti sem Hákon var vanur og hann kenndi honum ráð til. Nú … “og veit eg nú víst” segir hann, “að vér munum sigrast á þeim Jómsvíkingum … þvíað nú hefi eg heitið til sigurs oss á þær systur báðar, Þorgerði og Irpu, og munu þær eigi bregðast mér nú heldur en fyrr. |

In the end, the Jómsvíkings are defeated by the supernatural creature, which fought alongside her sister Irpa, summoned storms and threw arrows from each finger.

The Óláfs saga Tryggvasonar offers a very detailed narrative of the battle but is brief when referring to the sacrifice after the main battle’s narrative:

| It was rumoured that in this battle Jarl Hákon had made a sacrifice of his son Erlingr for victory, and after that the storm blew up, and then the casualties turned against the Jómsvíkings. | Þat er sǫgn manna, at Hákon jarl hafi í þessarri orrostu blótit til sigrs sér Erlingi, syni sínum, ok síðan gerði élit ok þá snøri mannfallinu á hendr Jómsvíkingum. |

Saxo, as usual, differs from the other sources in all imaginable ways. His narrative on Jarl Hákon’s sacrifice is almost as shorter as Snorri’s but utterly different in tone and intent. Judgemental and unapologetically interpretative, Saxo tells us that

| Hákon … turned, supposedly, to divine aid, and set about appeasing the powers above with a rare propitiatory offering. Bringing his own two sons, both of outstanding ability, to the altar like victims, he slaughtered them in an abominable sacrifice to secure victory… Have you ever heard of anything more stupid than this king? | Quorum Haquinus perspectis copiis, cum intolerabile rebus suis onus imminere cognosceret, excipiendi eius materia non suppetente tanquam humane opis diffidentia diuinam amplexus, superos inusitato piaculo propitiandos curauit. Duos siquidem prestantissime indolis filios hostiarum more aris admotos potiende uictorie causa nefaria litatione mactauit. Nec sanguinis sui interitu regnum emere dubitauit, patrisque nomine quam patria carere maluit. Sed quid hoc rege stultius, qui geminanV charissimorum pignorum stragem incertis unius pugne euentibus impendendo fortunam belli parricidio petere et orbitatem suam muneris loco diis bellorum fautoribus erogare sustinuit? |

There is, therefore, a large group of sources, independent to some degree, retelling the tradition around Jarl Hákon. This corpus was widespread enough for the stories to be retold from Denmark and Norway to Iceland.

In general, these sources agree on the central characteristics of some of the characters and the reality of human sacrifices in the Viking Age but have different goals.

Kurlandly will always offer free quality content without charging for it. Our primary intent is to divulge quality knowledge and transcend the boundaries of the academy. You can help us to make available more quality content quicker, acquiring some sustainable merch – such as a minimalist Viking T-shirt depicting Óðinn and Sleipnir – from our online store. Check it out!

1 Rudolf Simek, “The Sanctuaries in Uppsala and Lejre and their Literary Antecedents,” Religionsvidenskabeligt Tidsskrift 74 (2022): 217-230 at 224f.

2 Sverre Bagge, Society and Politics in Snorri Sturluson’s Heimskringla (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991), 24-6.

3 Steinsland, Gro, Norrøn religion: Myter, riter, samfunn (Oslo: Pax, 2005), 200f.

4 Ynglingasaga, trans. Finlay & Faulkes, ch. 09, p. 13; Ynglingasaga, ed. Bjarni Aðalbjarnarson, 22f; See also Christopher Abram, Myths of the Pagan North (New York: Continuum International Publishing Book, 2011), 248.

5 Ynglingasaga, trans. Finlay & Faulkes, ch. 25, p. 27; Ynglingasaga, ed. Bjarni Aðalbjarnarson, 47-49.

6 Gautrek’s Saga and Other Medieval Tales, trans. Hermann Pálsson and Hermann and Paul Edwards (London: University of London Press, 1968), 40.

7 Rudolf Simek, Lexikon der germanischen Mythologie (Stuttgart: Kröner, 1984), 283.

8 Olof Sundqvist, “Snorri Sturluson as a historian of religions – The credibility of the descriptions of pre-Christian cultic leadership and rituals in Hákonar saga góða,” in Snorri Sturluson – Historiker, Dichter, Politiker, ed. Heinrich Beck, Wilhelm Heizmann, and Jan van Nahl, 71-92 (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2013), 81f.

9 “Hákonar saga góða, in “Heimskringla. Vol I: the beginnings to Óláfr Tryggvason, trans. Alison Finlay, and Anthony Faulkes, 88-119 (University College London: Viking Society for Northern Research, 2011), ch.17-18, pp.101f; Snorri Sturluson. “Hákonar saga góða,” in Heimskringla, ed. Bjarni Aðalbjarnarson, Íslenzk Fornrit vol. 26: Heimskringla I (Reykjavik: Hið Íslenzka Fornritafélag, 1941),172f.

10 Ynglingasaga, trans. Finlay & Faulkes, ch. 15, p. 08; Ynglingasaga, ed. Bjarni Aðalbjarnarson, 31f.

11 Guta Lag and Guta Saga: The Law and History of the Gotlanders, ed. Christine Peel (Routledge, 2015), 278.

12 Eyrbyggja saga: Brands þáttr ǫrva, Eiríks saga rauða, Groenlendinga saga, Groelendinga þáttr, eds. Einar Ólafur Sveinsson and Matthías Þórðarson, Íslenzk fornrit 4 (Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag, 1935), 18.

13Íslendingabók Landnámabók, 2 vols, ed. Jakob Benediktsson, Íslenzk fornrit 1 (Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag, 1968), 126.

14 Vatnsdæla saga, ed. Einar Ólafur Sveinsson, Íslenzk fornrit 8 (Reykjavík: Hið íslenzka fornritafélag, 1939), 46.

15 See case by case discussed on Þórdís Edda Jóhannesdottir, “A Normal Relationship?: Jarl Hákon and Þorgerðr Hǫlgabrúðr in Icelandic Literary Context.” In Paranormal Encounters in Iceland 1150–1400, ed. Ármann Jakobsson and Miriam Mayburd, 295-310. The Northern World. (Boston & Berlin: De Gruyter & Western Michigan University Medieval Institute Publications, 2020), 301.

16 Morten Ravn, “Bronze and Early Iron Age Bog Bodies from Denmark”, in Acta Archaeologica, 81 (1: 2010), 112-113; Karen E. Lange. “Tales from the Bog,” in National Geographic, September 2007.

17 Per Holck. “The Oseberg Ship Burial, Norway: New Thoughts On the Skeletons From the Grave Mound,” European Journal of Archaeology 9 (August 2006): 185–210.

18 Lars Jørgensen, Lone Gebauer Thomsen, and Anne Nørgård Jørgensen, “Accommodating Assemblies, as Evidenced at the 6th–11th-Century AD Royal Residence at Lake Tissø, Denmark”, in Power and Place in Europe in the Early Middle Ages,ed. Jayne Carroll, Andrew Reynolds, and Barbara Yorke (Proceedings of the British Academy 224, 2019), 148–173 at 156-8. Se also frequent updates on the Nationalmuseet i København: “The magnate dynasty at Tissø”, <https://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/the-magnate-dynasty-at-tissoe/>, last access on 20 August 2022.

19 See Annette Lassen, “Hǫðr’s Blindness and the Pledging of Óðinn’s Eye: A Study of the Symbolic Value of the Eyes of Hǫðr, Óðinn and Þórr,” in Old Norse myths, literature and society: The proceedings of the 11th International Saga Conference, 2-7 July 2000, University of Sydney, Ed. Geraldine Barnes and Margaret Clunies Ross (Sydney: Centre for Medieval Studies, University of Sydney, 2000), 220-228 at 224f. Recent archaeological discoveries always in display at the Nationalmuseet i København: “Human sacrifices?” In: <http://en.natmus.dk/historical-knowledge/denmark/prehistoric-period-until-1050-ad/the-viking-age/religion-magic-death-and-rituals/human-sacrifices/>, last access on 20 August 2022.